Te hāngai me te kauneke

Alignment and progression

“What and how students learn depends to a major extent on how they think they will be assessed. Assessment practices must send the right signals…” (Biggs, 1999, p. 141)

“So assessment methods and assessment criteria must be properly aligned with both (a) intended learning outcomes and (b) desired kinds of online activity.” (Goodyear, 2001, p. 147)

On this page

- Designing alignment

- Writing Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

- Structured progression

- Types of assessment

- Over-assessment

- Feedback and feedforward

- Scalability: Providing good feedback without increasing workload

- Writing assessment criteria: Marking guides and rubrics

- Rubrics

- Types of rubrics

- Strategic links

- Useful tools

Designing alignment

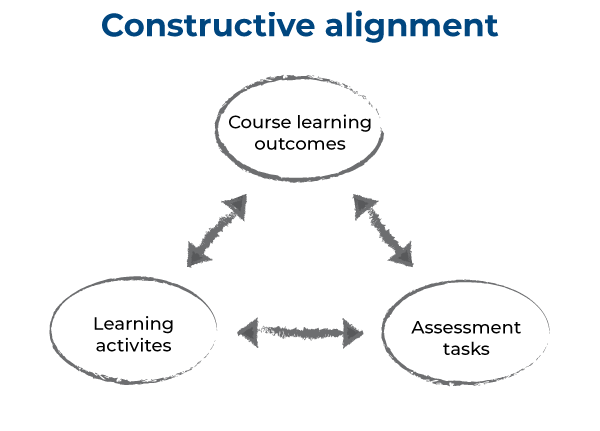

Alignment between learning outcomes, assessment tasks and learning activities is the crux of good course design. There are three main areas to consider when (re)designing assessment tasks:

- Consider the graduate profile capabilities, what students will need to be able to demonstrate by the end of the course, and students’ prior knowledge and experience, to define appropriate learning outcomes.

- Design learning experiences that help students build capability towards achieving intended learning outcomes.

- Design appropriate assessment tasks that enable students to demonstrate their achievement.

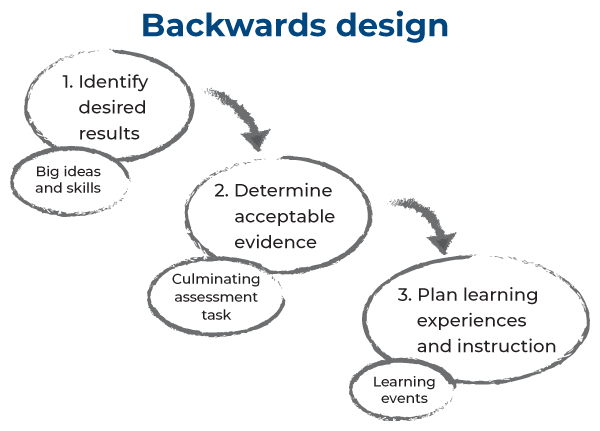

Two commonly used approaches to guide this process are ‘backwards design’ (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998) and ‘constructive alignment’ (Biggs, 1996).

Fig. 1 Backwards design. Image adapted from: https://slcconline.helpdocs.com/course/what-is-backward-design

The Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs) and Graduate Profiles (GPs) are the starting point and the heart of a course, from which the assessment and course activities should be derived.

First, focus on what your students need to be able to demonstrate they have learned at the end of your course. And how will they demonstrate these things?

Once you have defined what students need to be able to do to demonstrate their learning, the rest of your planning will focus on how you help them reach that point. Devise tasks that allow the learner to build and provide evidence of these abilities. Every one of your ILOs should be scaffolded and evidenced at some point in your course. Tasks (assessed or not) may be designed to develop and demonstrate more than one ILO/ GP.

Writing intended learning outcomes

Learning outcomes have three elements (Lincoln University, n.d.):

- An action verb describing the behaviour (what the student will do) which demonstrates the learning.

- Information about the context for the demonstration.

- The level at which the outcome will be demonstrated.

Ideally a good learning outcome is specific, measurable and defined in a way that is easily understood.

Example:

ERST 1XX: Perspectives on the environment

Course aim: To provide students an understanding of the meaning and relevance of the interrelationships between the ecological, cultural and economic dimensions of the environment by using a Systems Analysis framework.

Key learning outcomes: By the end of this subject, each student will be able to:

- Identify and define the key terms and components related to Systems Analysis.

- Identify at least three different perspectives on the environment.

- Explain the relevance of world views and science in understanding different perspectives on the environment.

- Identify and explain the relevance of the three dimensions (i.e., biophysical, sociocultural, and economic) of the environment.

- Apply a Systems model to a real-world example.

- Follow and map an environmental issue using Systems Analysis principles.

From Lincoln University: https://tlc.lincoln.ac.nz/writing-good-learning-outcomes

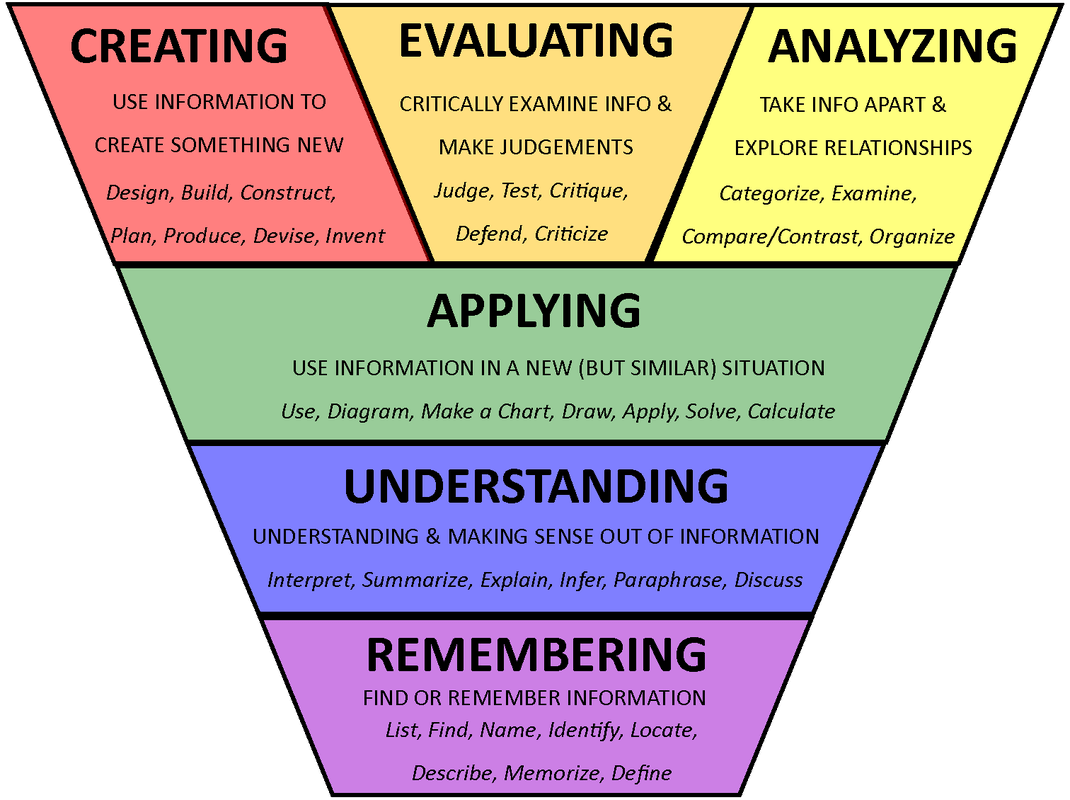

The verb used to describe what the student will do to demonstrate learning should be a concrete action verb (e.g., identify) rather than an abstract action verb (e.g., understand).

Bloom’s revised taxonomy (cognitive domain), provides some guidance on the kind of action verbs you may wish to use in developing your ILOs to describe how students can demonstrate their learning.

Fig. 3 Bloom’s Taxonomy, revised version. From: Hos-McGrane, M. (2014). Flipping Grade 4 and Flipping Bloom’s Taxonomy Triangle. Tech Transformation. http://www.maggiehosmcgrane.com/2014/09/flipping-grade-4-and-flipping-blooms.html

The image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Note: Bloom’s model has been criticised on various levels and has been through a number of revisions, but it still serves as a good introduction to thinking about desired outcomes.

Bloom’s Taxonomy (descriptive)

Bloom’s Taxonomy categorises six educational goals along a continuum from simple to complex, concrete to abstract (Armstrong, 2010).

| Level & Cognitive Domain | Expectation | Action Verbs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Remembering | Retrieving, recalling or recognising knowledge from memory. | Define, describe, identify, label, list, match, name, outline, reproduce, select, state, recall, record, recognise, repeat draw on, recount… |

| 2. Understanding | Showing understanding by interpreting what is known in one context when used in another context. | Estimate, explain, extend, generalise, paraphrase, rewrite, summarise, clarify, express, review, discuss, locate, report, identify, illustrate, interpret, represent differentiate… |

| 3. Applying | Carrying out or using a procedure through executing or implementing. | Apply, change, compute, calculate, demonstrate, discover, manipulate, modify, operate, predict, prepare, produce relate, show, solve, use, schedule, employ, sketch, intervene, practise, or illustrate…. |

| 4. Analysing | Breaking material or concepts into parts, determining how the parts relate or interrelate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose. | Analyse, diagram, classify, contrast, categorise, differentiate, discriminate, distinguish, inspect, illustrate, infer, relate, select, survey, calculate, debate, compare, criticise… |

| 5. Evaluating | Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing. | Appraise, argue, compare, conclude, contrast, criticise, discriminate, judge, evaluate, revise, select, justify, critique, recommend, relate, value, validate, summarise… |

| 6. Creating | Putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganising elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning or producing. | Compose, design, plan, assemble, prepare, construct, propose, formulate, set up, invent, develop, devise, summarise, produce… |

From: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy (Revised version – credit Anderson and Krathwohl 2001)

SOLO Taxonomy (descriptive)

Biggs and Collis (1982) describe a means of classifying learning outcomes in terms of their complexity, the SOLO Taxonomy. SOLO stands for Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome.

| Level & Cognitive Domain | Description | Action Verbs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-structural | Students are acquiring bits of unconnected information, which have no organisation. | |

| 2. Uni-structural | Simple and obvious connections are made, but their significance is not grasped. | Define, describe, list, identify, name, follow procedure… |

| 3. Multi-structural | A number of connections may be made, but the meta-connections between them are missed, as is their significance for the whole. | Combine, describe, enumerate, list… |

| 4. Relational | The student is now able to appreciate the significance of the parts in relation to the whole. | Analyse apply, argue, compare/contrast, criticise, explain, justify, relate… |

| 5. Extended abstract | Connections are made within the given subject area and beyond it, able to generalise and transfer the principles and ideas underlying the specific instance. | Create, formulate, generate, predict, theorise, hypothesize, reflect… |

From: https://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/ (Biggs and Collis, 1982)

Structured progression

Ideally the assessment plan will be devised across all courses in a programme to build student capabilities incrementally across courses. But while this is not always feasible, a course assessment plan should be reviewed against other courses in the programme to ensure alignment throughout.

You might find useful a set of holistic rubrics, developed for the Business School to support staff in understanding the progressive nature of capability development across the curriculum stages. N.B., these were related to the implementation of the Graduate Profiles prior to the changes that are underway in 2022.

Assignment tasks should cumulatively develop the learner’s ability to produce the required evidence to satisfy learning outcomes through a structured progression of tasks that build capability incrementally. These tasks need to be timed to enable the learner to complete the various stages and receive feedback in time to process and act on it in the final assessment task.

Early in the course, students need a low stakes/ungraded opportunity to try (and fail, in a safe environment) a small component of the kind of task that will be assessed. This should be a building block for the final assessment task; an opportunity to practise the first stage of the required outcome.

The final point of assessment, albeit summative, should provide an opportunity for reflection on the student’s learning journey: where they began and how their perceptions/ skills have changed.

You might think of your course assessment as a koru frond, with a succession of formative tasks that build on each other and scaffold learning, through feedback, to the final summative assessment.

Types of assessment

Assessments are intended to measure knowledge acquisition, performance and capability development and must be aligned with intended learning outcomes. There are two main types of assessment (Ministry of Education, n.d.):

- Formative assessments – conducted at specific intervals throughout a course to give students feedback on their performance and to give teachers information on how students are learning.

- Summative assessments – conducted for the purpose of assigning a grade.

There are further types, including diagnostic—often used prior to a course as a benchmark or to ascertain a starting point, and ipsative—in which the student is compared against themselves (e.g., a past performance) rather than against others (normative), but essentially, assessment tasks either provide information for feedback and feedforward, or they are designed to measure outcomes. They may also do both. A balance between formative, summative and ipsative feedback such as in Portfolio-based assessment allows assessors to balance the three types/ modes.

Another way of thinking about various types of assessment and their function in learning is:

Assessment of learning

- Evidence of learning against intended outcomes.

- A snapshot of learning at a specific point in a course.

- Summative: Assignment, test, or exam.

Assessment as learning

- Empower and engage students in the assessment process.

- Opportunities for students to practise/perform the intended outcomes.

- Build agency, self-assessment, and goal setting skills.

- Foster self-reflection and self-managed learning.

- Improve metacognitive skills and application of knowledge.

- Usually formative: May be self-assessment questions/quizzes, practice assignments, optional review exercises.

Assessment for learning

- Gain feedback and feedforward, to evaluate and monitor progress.

- Formative: may be report or essay outlines, first drafts, to identify gaps in understanding or alter course delivery.

We can assess before (diagnostic tests, activation of prior knowledge), during and/or after learning. Assessment can happen in class or outside class, online or offline, (e.g. field work, practicum, group or individual project …)

Who can assess student learning?

Teachers, students and/ or students’ peers can do the assessing. Engaging students in self and peer assessment can be effective ways to develop critical thinking and objective analysis.

Giving students the opportunity to co-design tasks and/or assessment criteria can be a powerful way of increasing engagement and developing critical thinking skills.

Over-assessment

It is easy to fall into the trap of over-assessing students. Common reasons we end up overloading students are:

- We want to be sure we give students ample opportunity to demonstrate they have achieved the intended learning outcomes, so we assign multiple assessment tasks.

- We create discrete, small tasks that measure only a fragment of the desired achievements, so we feel we need to add more.

- We ‘split’ tasks into multiple parts (e.g., Assignment 1A, 1B etc.) to ‘squeeze in’ more without seemingly having too many.

- We offer multiple, small incentives to complete a lot of formative assessment tasks, for example participation in a discussion, plussage, or additional marks for doing a quiz.

Over-assessing creates unnecessary stress and pressure on workloads for both staff and students. Student overload is also a common motivating factor for academic dishonesty, so addressing over-assessment can help cultivate an environment that supports academic integrity. Remember that students are juggling many aspects of life, not only their study. Flexibility is key and assessment strategies that allow students to build skills over time are preferable to snapshots in time and fixed-time tests.

Common workarounds for over-assessment are:

- Review the number of formative and summative assessment tasks and how they inform one another. As a general guideline, 2-3 summative tasks are recommended at the University of Auckland, although multiple smaller tasks can be set as formative tasks to allow the development of the skills needed in summative tasks.

- Consider the assessment load for students horizontally across the programme, during the semester. Are there opportunities for skills development in one course to be complemented by skills development in a concurrent course?

The ‘cognitive walkthrough’ technique may help you decide if you are over-assessing (Goodyear, 2001). This essentially means putting yourself in the students’ place and mentally stepping through the course, or in this case assessment tasks, to get a feel for how long it would take and how clear the instructions are.

One way to determine how your topics and assessments are staggered throughout the course, is to map them to a grid. This course mapping template may help. It is a Microsoft Word document comprising assessments and learning activities as draggable boxes. The idea is that you align them to a weekly structure to determine the expected student workload, while paying attention to whether the grade allocations are fair.

Example course map Word doc

Course map template Word doc

Feedback and feedforward

“While feedback focuses on a student’s current performance, and may simply justify the grade awarded, feed forward looks ahead to subsequent assignments and offers constructive guidance on how to do better. A combination of both feedback and feed forward helps ensure that assessment has a developmental impact on learning.

Effective feedback should also stimulate action on the part of the student. The most effective practice treats feedback as an ongoing dialogue and a process rather than a product.” (JISC, 2015)

Feedback and feedforward are the primary means by which learners can assess what they need to work on and gauge their progress, so small tasks with lots of feedback early on helps make this path clear.

Students need (Absolum, 2006):

- Clarity about what learning is intended: What am I trying to learn here and why?

- Clarity about the criteria for the learning: How do I know when I have learnt and to what standard?

- Opportunities to understand and use the criteria – self and peers: How well am I going? What do I need to do?

Formative feedback

Formative feedback (assessment for learning) provides opportunities for the learner to reflect on:

- What am I doing that is right?

- What am I doing that needs adjustment and further work?

Feedback therefore needs to focus on both: to specify achievement and identify pathways to improvement. It is important that all (teachers, learners and peers):

- Understand the criteria and the standards.

- Have access to exemplars/ models/ external points of reference.

It’s also crucial for learners to have:

- Time to practise and revisit ideas.

- Time to act on feedback.

- Opportunities for reflection and self-evaluation.

According to Hattie and Timperley (2007), the aim of feedback is “reducing the discrepancies between current understandings/ performance and a desired goal” (p. 86).

Feedback typically tells us how we are progressing towards a goal; feedforward should tell us what we need to do to get closer to it.

Effective feedback is:

- Timely – Provide feedback as soon as possible after students submit their assessment, while it is still fresh in their minds, and they have time to incorporate feedback into their next assessment.

- Actionable – Provide concrete information and suggest strategies for improvement. Value-based statements such as “Excellent” or “Well done” do not help students understand why they did well or how to improve.

- Aligned to learning outcomes and assessment criteria – Connect feedback to the learning outcomes and the specific criteria in the marking rubric.

For more on effective feedback, including timing and how to avoid possible negative effects, see:

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F003465430298487

Summative feedback as teaching quality indicators

Summative feedback (assessment of learning) is usually thought of as the final grade a student is awarded, usually with no indication of how these may have been improved.

However, for teaching staff, assessment data can be used for continuous enhancement to:

- Evaluate the quality of the teaching and learning experiences to improve teaching.

- Report the learning to a range of audiences to prove learning.

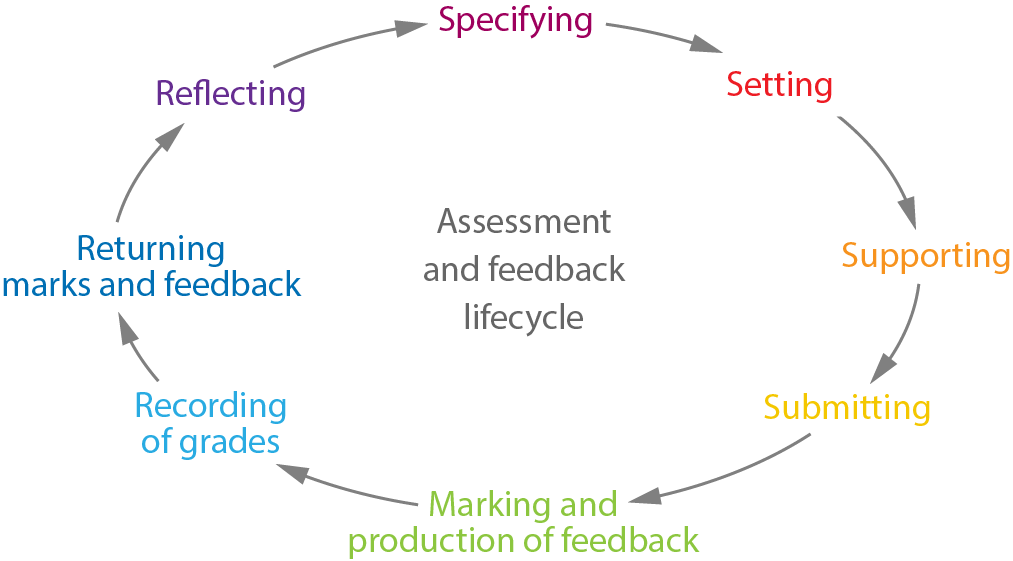

As Graeme Aitken (University of Auckland) noted in his presentation on TeachWell, “the assessment data from your course is also the most useful measure of teaching effectiveness. Use assessment data to identify areas for improvement, making changes and measuring assessment data – by question, by type, by subgroup….” This is indicated by the ‘reflecting’ part of the diagram in figure 5.

Fig. 5 The assessment and feedback life cycle for the academic (adapted from an original by Manchester Metropolitan University). CC BY-NC-SA, reproduced from JISC.

Scalability: Providing good feedback without increasing workload

Generic + short personal feedback

Giving generic feedback to the class, alongside a short, personalised comment to individuals can help with marking workload whilst giving students an idea of what good quality assignments looked like.

Example:

Feedback to class: “I was impressed by the extent to which some of you researched this question. On the whole most of you managed to identify …. which were…. The best answers were those that ….”

Feedback for individual student: “You did a good job of comparing … a little more reference to theory and research would have further strengthened this.”

Video or audio feedback can also be useful – students report that it feels more personal and lecturers that it can be quicker. This can be done in Canvas’ SpeedGrader.

Develop students’ skills in self-regulation and self-reflection

Common issues with assessment and feedback identified by JISC include under-developed abilities in self-regulation and self-reflection. Developing these as part of designing and scaffolding for assessments using constructive alignment can result in long-term positive effects on lecturer workload.

David Nicol talks about the importance of activating learners’ own judgement of their work by providing opportunities for them to compare their work with exemplars or the work of peers. His research claims that analogical comparisons (comparing your work against similar work) is often better than analytical comparison (comparing your work against criteria, or against feedback comments). By staging multiple opportunities for comparison throughout the course, he claims there is a cumulative benefit – and there is no additional workload involved. In fact, the lecturer makes fewer written feedback comments.

As Nicol puts it, “it’s just about selecting the right comparator, depending on where you think students might have difficulty…. All one needs to do is to ask the students … to think about what they could do to improve their own work,” and then make it explicit.

Click the Full screen button or Watch on YouTube for a larger view.

More information on the role of comparison in learning from feedback:

- Guiding learning by activating students’ inner feedback - David Nicol.

- Nicol, D. (2021). The power of internal feedback: exploiting natural comparison processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(5), 756-778. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2020.1823314

Gavin Brown (University of Auckland) points out that while feedback should provide the student with information about what to do next, the ‘driver has to pay attention’. He suggests that time and motivation are needed for students to engage with feedback—and motivation is lacking if feedback on task 1 is totally unrelated to task 2, or to summative assessment.

Gavin’s presentation was recorded on 22 September 2021 at the University of Auckland’s Academic Psychology Colloquium.

Click the Full screen button or Watch on YouTube for a larger view.

Writing assessment criteria: Marking guides and rubrics

Marking Guides and Rubrics contain criteria that describe the standards you are looking for in an assessment. They guide students around what you expect them to do and can also ensure consistency in marking processes. There are some differences between the two:

- Marking guides include somewhat vague criteria to enable more flexibility for the marker to judge the quality of the assessment.

- Rubrics are pre-set scoring sheets that specify the precise standards required to meet each grade.

Marking guides

Marking guides are useful when the assessment has no single correct answer or where creativity, translation, or other less precise, pre-determined ability is required. Marking guides allow the marker to evaluate and provide individualised comments on the learner’s interpretation of the task.

Example assessment

Criteria Entries demonstrate:

- Evidence of analytical and critical thinking.

- Evidence of reflective thinking about own understanding of the role of a teacher.

- Ability to relate and synthesise course content in relation to own practice, values and beliefs.

- Ability to write concisely, precisely and coherently.

- References to the literature in accordance with APA style.

Table 1

| D range 0-15 | C range 15-19 | B range 20-23 | A range 24-30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interprets theory accurately |

Limited understanding Many errors |

Some understanding Several errors |

Accurate understanding Some errors |

Accurate understanding Few/ no errors |

| Presents critique of the article and its relationship to theory | Limited or at superficial level | Some ideas raised and explored | Several ideas raised and explored | Many ideas raised and explored |

| Addresses ideas concerning diversity of students | Limited or at superficial level | Some ideas raised and explored | Several ideas raised and explored | Many ideas raised and explored |

| Uses APA referencing conventions |

Inadequate/ minimal use of references Inadequate/ minimal use of conventions |

Some use of references Uses correct conventions – many refinements needed |

A range of references Uses correct conventions – some refinements needed |

Acknowledges a wide range of references Uses conventions consistently with few/ no errors |

Advantages

- Marking guides offer more flexibility and allow markers to reward creative and unpredicted responses.

Disadvantages

- A marking guide is open to subjective judgement and so assessment can be much more variable/ contestable.

- May result in inconsistencies across marking teams.

Rubrics

There are many different types of rubrics for marking. The more detailed a rubric is in terms of allocated grade and description, the more precise it is. The use of rubrics can improve consistency amongst multiple markers. Pre-defined grades with specific criteria can also speed up marking, as there is little subjective judgement required.

Here we provide guidance on creating a rubric.

Table 2

| Criteria | 1 Below standard | 2 Approaches standard | 3 Meets standard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Selection & clarity of criteria (rows) | Criteria being assessed are unclear, have significant overlap, or are not derived from appropriate standards for product/ task and subject area. | Criteria being assessed can be identified, but not all are clearly differentiated or derived from appropriate standards for product/ task and subject area. | All criteria are clear, distinct, and derived from appropriate standards for product/ task and subject area. |

| Distinction between levels (columns) | Little or no distinction can be made between levels of achievement. | Some distinction between levels is clear, but may be too narrow or too big of a jump. | Each level is distinct and progresses in a clear and logical order. | |

| Quality of writing | Writing is not understandable to all users of the rubric, including students; it uses vague and unclear language which makes it difficult for different users to agree on a score. | Writing is mostly understandable to all users of the rubric, including students; some language may cause confusion among different users. | Writing is understandable to all users of the rubric, including students; it uses clear, specific language that helps different users reliably agree on a score. | |

| Use | Involvement of students in rubric development* | Students are not involved in development of rubric. | Students discuss the wording and design of the rubric and offer feedback/ input. | Teachers and students jointly construct the rubric, using exemplars of the product or task. |

| Use of rubric to communicate expectations & guide students | Rubric is not shared with students. | Rubric is shared with students when the product/ task is completed, and used only for evaluation of student work. | Rubric serves as a primary reference point from the beginning of work on the product/ task, for discussion and guidance as well as evaluation of student work. |

* Considered optional by some educators and a critical component by others.

Rubric adapted from Dr. Bonnie B. Mullinix, Monmouth University, NJ

© 2012 Buck Institute for Education

Source: Rubric for rubrics @ Buck Institute for Education

Example rubric

Table 3

| Grade | Mark allocation | Descriptor |

|---|---|---|

| A+ | 19 – 20 |

Response demonstrates an in-depth reflection on the specified learning event. Clear linkages are made to the reflective practice model, relevant group work processes/ dynamics/ concepts and awareness skills used in the course. Interpretations are insightful and all observations made are well supported by relevantly selected sources. Clear, detailed examples of the event are provided, and their impact on the personal/ professional use of self-explained. Writing is soundly structured, sequenced and easy to follow. The annotation is free of grammatical, spelling and punctuation errors. APA is correctly applied. |

| A | 17 – 18 | |

| A- | 16 – 16.5 | |

| B+ | 15 – 15.5 |

Response demonstrates a general reflection on the specified learning event. Linkages, in the main are made to the reflective practice model, relevant group work processes/ dynamics/ concepts and awareness skills used in the course. Interpretations are supported. Appropriate examples are provided, as relevant. Implications of these insights for the personal/ professional use of self are presented. Writing is mostly clear, concise and well structured. Mistakes in spelling, grammar and APA referencing style are rare. |

| B | 14 – 14.5 | |

| B- | 13 – 13.5 | |

| C+ | 12 – 12.5 |

Response demonstrates minimal reflection on the specified learning event. Linkages to the reflective practice model, relevant group work processes/ dynamics/ concepts and awareness skills used in the course are sparse. Interpretations are insufficiently supported. Examples are rarely used. Insights are minimal and their implication for the personal/ professional use of self is patchy. Established academic writing protocols are not well met, e.g., writing is unclear; content is not well synthesised; thoughts are not logically expressed; high rate of grammar and spelling mistakes. APA incorrectly applied. |

| C | 11 – 11.5 | |

| C- | 10 – 10.5 | |

| D+ | 9 – 9.5 |

Response demonstrates absence of reflection on the specified learning event. Scant linkage is made to the reflective practice model, relevant group work processes/ dynamics/ concepts and awareness skills used in the course. Interpretations are not supported. Examples aren’t used, when applicable. No insights are offered and no connection to the personal/ professional use of self is offered. Academic writing protocols are not observed. Writing is unclear and disorganised. Numerous errors in spelling and grammar is present and APA is incorrectly applied, if used. |

| D | 8 – 8.5 | |

| D- | 0 – 7 |

Advantages

- In general, the more specific and clear the rubric the less contestable/ variable/ subjective the assessment will be.

- Rubrics enable more consistency across a range of markers.

- Rubrics are considered by some to be fairer and more transparent for the learner with a clearly visible grading structure for the student to follow.

Disadvantages

- Rubrics may limit creativity and divergent thinking as criteria are pre-set. For example, a wonderful, innovative idea might easily score 0% if it had not been predicted and accounted for in the criteria.

Types of rubrics

Holistic rubrics

Holistic rubrics describe standards that students are expected to progressively achieve over an entire programme. Holistic rubrics provide a means of evaluation that can be consistently applied across entire student cohorts to assess and grade multiple skills and tasks students may be required to demonstrate, such as critical thinking and collaborative teamwork.

The University of Auckland’s Business School created examples of holistic rubrics which include standards that can be easily adapted to meet the needs of any student cohort.

Analytical rubrics

An analytical rubric is a more specific multi-layered type of rubric used to assess complex learning based on several criteria, each of which is described at several levels of performance.

The TeachWell website provides a great deal more on providing effective feedback, feedback tools, and rubrics and criteria in Canvas.

Strategic links

The theme of Alignment and progression relates to the TeachWell core capabilities:

- Aligning intended learning outcomes, teaching approach and assessment.

- Providing feedback to students that is helpful, timely and constructive.

- Designing assessment opportunities that enable students to develop and demonstrate their capabilities.

… and the University’s principles of assessment:

- 2. Assessment design is coherent and supports learning progression within courses and across programmes.

- 3. Assessment tasks are demonstrably aligned with course-level learning outcomes, and programme and University-level Graduate Profiles.

- 6. Feedback is timely and provides meaningful guidance to support independent learning.

Useful tools

- Writing Good Learning Outcomes (Lincoln University).

- Planning tools and templates can help to ensure all ILOs are aligned with assessment and to see where one assessment task builds on a previous one.

- Providing effective student feedback (Remote Learning website).

- Holistic rubrics (Business School, the University of Auckland. Shared with permission from the developers; Nabeel Albashiry and Mark Smith).

The theme of Alignment and progression links with the values and principles of:

Manaakitanga

Caring for those around us in the way we relate to each other.

How we design characterises how we care for our students. Taking care to ensure a structured progression of learning and not over-assessing demonstrates a human-centred approach to teaching and learning, including recognising students are people with other life responsibilities and commitments. Providing low stakes opportunities in assessment makes it safe to try, fail, and learn, fostering bravery in learning.

Whanaungatanga

Recognising the importance of kinship and lasting relationships.

Whanaungatanga is at the heart of good learning experiences. Developing good relationships between students and teachers, and between students themselves, can help people feel connected and supported in their learning. We develop this through a bond of trust, where both teachers and students know we are working together for everyone to succeed. When we give constructive and supportive feedback, it is the whanaungatanga we have developed and our care and high expectations for our students’ capabilities that makes it meaningful to them and supports them in their learning.

Excellence

We believe that excellence in teaching and research provides a means of engendering transformation in the lives of many people.

How we design learning experiences helps students build their capabilities. Assessment as learning empowers and engages students in their learning. More than just a method of demonstrating student achievement of the intended learning outcomes in a course, assessment provides opportunities for the personal development of the student as a whole person for their future, and for the benefit of their communities.

Additional resources

- Getting Started with writing learning outcomes (Cornell University).

- Learning outcomes review checklist (Cornell University).

- Checklist for student learning outcomes (NACADA).

- Writing learning outcomes: A practical guide for academics (University of Melbourne).

- Learning outcomes and rubrics in Canvas (University of Auckland: Video 13:34).

- Feedback principle: Aligned (University of Wollongong: Video 02:41).

- Aligning assessment with outcomes (UNSW Sydney).

- Assessment resources (Trinity College Dublin).

References

Absolum, M. (2006). Clarity in the classroom. Auckland: Hodder Education.

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Biggs, J. B., & Collis, K. F. (1982). Evaluation the quality of learning: the SOLO taxonomy (structure of the observed learning outcome). Academic Press.

Goodyear, P. (2001). Effective networked learning in higher education: notes and guidelines (Deliverable 9). Bristol, UK: Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC).

Goodyear, P., Avgeriou, P., Baggetun, R., Bartoluzzi, S., Retalis, S., Ronteltap, F., et al. (2004). Towards a pattern language for networked learning. In S. Banks, P. Goodyear, V. Hodgson, C. Jones, V. Lally, D. McConnell & C. Steeples (Eds.), Networked learning (pp. 449-455). Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F003465430298487

JISC. (2015). Feedback and feed forward. Transforming assessment and feedback with technology (p. 20). https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/transforming-assessment-and-feedback/feedback

Lincoln University. (n.d.). Writing good learning outcomes. Teaching and Learning Centre. https://tlc.lincoln.ac.nz/writing-good-learning-outcomes/

Ministry of Education, Te Tāhuhu o Te Māatauranga. (n.d.). Formative and summative assessment. Assessment online. https://assessment.tki.org.nz/Using-evidence-for-learning/Gathering-evidence/Topics/Formative-and-summative-assessment

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). What is backward design. Understanding by design, 1, 7-19.